Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction to Buddhism

- 2 What Is Buddhism and what are the main beliefs of Buddhism?

- 3 Founder of Buddhism: Who, When, Where?

- 4 What Are the Four Noble Truths?

- 5 Buddhism Global Distribution & Number of Followers

- 6 Buddhism vs. Christianity Fundamental Differences

- 7 The Most Sacred Buddhist Sites

- 8 The Eightfold Path: Theory

- 9 Buddhist Five Symbols & Meaning

- 10 The Eight Auspicious Symbols (Aṣṭamaṅgala)

- 11 Major Buddhist Texts

- 12 Modern Relevance & Conclusion

- 13 📚 Sources & References

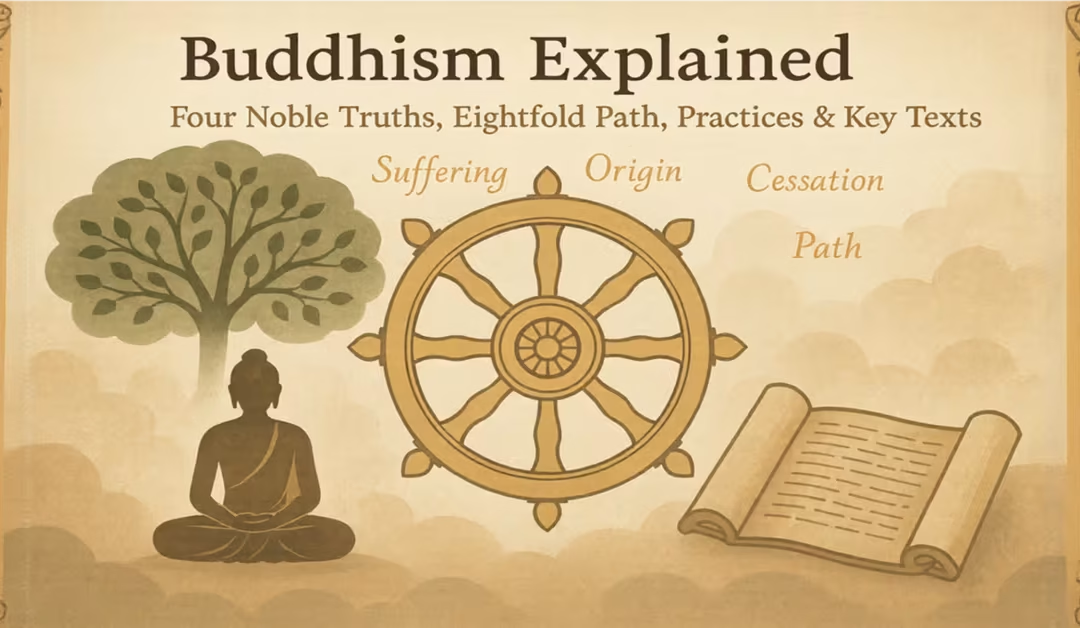

Introduction to Buddhism

Buddhism is an ancient spiritual path, discover the Four Noble Truths, Noble Eightfold Path, key texts & sacred sites. Learn how to practice and apply it today. Buddhism is an ancient spiritual path anchored in the deep human experience of dukkha, often translated as suffering, stress, or dissatisfaction. Rather than focusing on a creator deity or dogma, Buddhism offers practical tools for inner transformation—including compassion practices, mindfulness meditation, and the pursuit of liberation (nirvāṇa). Far from being a static, archaic tradition, Buddhism has demonstrably influenced modern psychology, especially in the development of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mental health therapies.

As of 2020, approximately 342 million people—about 4% of the world’s population—identify as Buddhists. That figure remains significant even amid global secularization, especially in East Asia. Across continents, Buddhists engage in diverse practices—ranging from Theravāda chanting and Zen meditation to Tibetan tantric rituals—balancing introspection with communal devotion.

In this comprehensive article, we trace Buddhism’s journey from its origin in ancient India to its present-day global presence. We’ll explore:

- What is Buddhism? Its core beliefs and worldview.

- Founder: Siddhārtha Gautama—his life, awakening, and teachings.

- Global footprint: How many followers exist, and where they are concentrated.

- Comparisons with Christianity and Hinduism to highlight distinctive features.

- Sacred sites: The four places central to Buddhist pilgrimage.

- The Eightfold Path: Both theory and detailed explanation.

- Key texts: From the Pāli Canon to Mahāyāna sutras.

- Symbols: Dharma wheel, lotus, stupa, and the Eight Auspicious Symbols.

What Is Buddhism and what are the main beliefs of Buddhism?

Buddhism is best described as a path of empirical insight and inner liberation, rather than a creed-based religion. Emerging around the 5th century BCE in South Asia, it centers on the idea that life inherently involves suffering—but that this suffering can be recognized, understood, and ultimately transcended through conscious effort. The practice revolves around three foundational pillars:

- Ethical conduct (sīla) – doing no harm, speaking truthfully, and leading a life of decency;

- Mental development (samādhi) – cultivating concentration and clarity through meditation practices like mindfulness (sati);

- Wisdom (paññā) – evolving a clear understanding of reality, especially the Four Noble Truths and the notion of no-self (anattā).

Far from being dogmatically atheist, Buddhism is non-theistic: it doesn’t deny the existence of gods but places primacy on personal responsibility and inner transformation. This marks a key distinction from many other spiritual traditions.

Even so, Buddhism encompasses rich devotional practices—chanting sutras, making offerings, observing festivals—all of which are integrated into the sangha (community), which includes both monastics and lay followers. The real-life expressions vary widely: Zen emphasizes silent meditation; Theravāda foregrounds monastic discipline and Pāli scripture; Tibetan traditions engage in tantric practices, offering vibrant visualizations and rituals. But despite differences, all branches share the promise of resilience, peace, and freedom as attainable in this very lifetime.

This adaptability has positioned Buddhism as a perennial bridge between ancient spiritual wisdom and contemporary seekers—whether one is practicing in a monastery or applying Buddhist mindfulness in the workplace.

Founder of Buddhism: Who, When, Where?

Buddhism traces its origin to Siddhārtha Gautama, who lived approximately 563–483 BCE in what is now Lumbini, Nepal. Born into the royal Shakya clan, his father is said to have shielded him from the suffering of the world, hoping he would become a great monarch. But at about age 29, Siddhārtha encountered the Four Sights—an old man, a sick man, a dead man, and a renunciant—which led him to question the meaning of life and power.

Renouncing his princely life, he pursued spiritual liberation through extreme ascetic practices for six years. Eventually, he embraced a Middle Way—avoiding both extreme indulgence and self-mortification—and achieved enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya, India, at age 35. This awakening marked his transformation into the Buddha, or “Awakened One.”

He spent the next 45 years teaching across northern India. Crucially, his first sermon at Sarnath, near Varanasi in 528 BCE, introduced the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path, setting in motion the Dharma (“turning of the wheel”). His life concluded in Kushinagar, India, where he passed into parinirvāṇa (final liberation). These four places—Lumbini, Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, and Kushinagar—became the backbone of Buddhist pilgrimage traditions.

Although his biography is woven from both documented events and spiritual legend, historical scholarship generally agrees these core details reflect reality, even as later texts added layers of mythic depth.

What Are the Four Noble Truths?

The Four Noble Truths constitute the essence of the Buddha’s first sermon and form the foundation of Buddhist philosophy:

1. Dukkha (Suffering): Acknowledge that life inherently involves suffering, dissatisfaction, and impermanence—through aging, illness, loss, and existential discontent.

2. Samudaya (Origin of Suffering): Understand that suffering arises from tanha—craving, attachment, desire, and ignorance.

3. Nirodha (Cessation): Realize that by letting go of craving, suffering can end—leading to liberation (nirvāṇa).

4. Magga (Path): Follow the Noble Eightfold Path—right understanding, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration—as the practical means to end suffering.

Who is Buddhism God?

Buddhism is technically non-theistic—it doesn’t posit a creator god who governs the universe or human destiny. However:

The Buddha is revered as a teacher—an enlightened being, sometimes called Bhagavā (“Lord” or “Blessed One”), but not a divine creator.

Buddhist cosmology includes powerful deities (devas, Bodhisattvas), like Brahmā or Mahākāla, but they are not eternal creators; they exist within samsara and eventually pass away.

Devotion in Buddhism is often directed toward enlightened beings as inspirations, not as supreme gods commanding worship.

Quick Buddhism Facts

Founder: Siddhārtha Gautama (the Buddha), 6th–5th century BCE, northern India/Nepal.

Global Population: Around 4% of the world (~342 million) identify as Buddhist.

- Branches:

- Theravāda (Sri Lanka, Thailand)

- Mahāyāna (China, Korea, Japan)

- Vajrayāna/Tibetan (Tibet, Bhutan)

Core Teachings: Four Noble Truths, Noble Eightfold Path, karma, rebirth, anattā (no-self).

Sacred Sites: Lumbini, Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, Kushinagar.

Symbols: Dharma wheel, lotus, stupa, Bodhi tree.

Practice Methods: Meditation (samatha & vipassanā), chanting, ethical precepts, rituals, devotional offerings.

Modern Emphasis: Mindfulness, secular adaptations, social engagement, and interfaith dialogue.

How to Practice Buddhism?

Learn the Basics: Study foundational teachings: the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. Start familiarizing yourself with texts like the Dhammapada.

Adopt Ethical Precepts: Begin with the basic five—no killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, or intoxicants. These support a moral foundation.

Cultivate Mindfulness & Meditation: Practice daily meditation: e.g., 10–20 minutes focused on the breath. Extend mindfulness into daily tasks—walking, eating, working—observing the present moment .

Engage with Community (Sangha): Join a local temple, meditation center, or online sangha for guidance, group practice, and connection.

Deepen Insights: Study Buddhist literature: Dhammapada, suttas, or Mahāyāna sutras. Reflect on impermanence, suffering, and no-self during meditation and daily life.

Live Mindfully: Apply the Eightfold Path in everyday life: practice right speech, right livelihood, right effort, and more .

Participate in Rituals (Optional): Chant, bow to a Buddha statue or Bodhi tree—not as divine worship but as acts of reverence and reminder.

Boxed Insight from Reddit:

“I don’t pray to Buddha. I thank him for finding and sharing the path to enlightenment.” (reddit.com)

“A good way to establish the foundation… is with the ten virtuous actions… Meditation is also useful… The best way… is with other Buddhists.” (reddit.com)

Buddhism Global Distribution & Number of Followers

As of 2020, 342 million people worldwide—approximately 4% of the global population—identify as Buddhists. Though earlier estimates ranged from 488 million (7%) in 2010 to a high of 535 million (8–10%), global secularization, especially in East Asia, has contributed to a decline in self-identified Buddhists. Pew Research projects that by 2050, the Asia‑Pacific region will still house 98–99% of Buddhists, although the total population may decrease slightly in proportion.

Regional & National Followers

- China holds the largest Buddhist population at around 244 million, accounting for 18% of its population. Predominantly Mahāyāna Buddhism, this demographic swing boosts global figures.

- Southeast Asian nations show high adherence:

- Cambodia: 96.8%

- Thailand: ~92.6%

- Myanmar: ~79.8%

- Bhutan: ~74.7%

- Sri Lanka: ~68.6%

- Laos: ~64%

- Mongolia: ~54.4%

- In East Asia:

- Japan: Estimates vary from 20–36%, depending on religious affiliation and cultural practice.

- Singapore: ~32.2%

- South Korea: ~21.9%.

- Other significant populations include Vietnam, Taiwan, Nepal, and pockets within Russia (e.g., Tuva, Kalmykia, Buryatia).

Overall, Asia-Pacific contains about 99% of global Buddhists, with North America (~3.9 million) and Europe (~1.3 million) hosting much smaller communities. These diasporic communities, though small in percentage, have catalyzed a Western embrace of Buddhist mindfulness, meditation, and secular spirituality.

Buddhism vs. Christianity Fundamental Differences

Theism: Buddhism is non-theistic; Christianity is monotheistic with belief in a personal Creator God.

Salvation/Grace: Buddhism emphasizes self-effort and karmic consequences; Christianity depends on divine grace and redemption through Christ’s sacrifice.

Afterlife: Buddhism teaches cyclical rebirth based on karma; Christianity teaches resurrection followed by heaven or hell via divine judgment.

Eschatology: Buddhism envisions endless samsara without final apocalypse; Christianity expects a Last Judgment and end of creation.

| Aspect | Buddhism | Christianity |

| God | Non-theistic | Monotheistic |

| Ultimate Goal | Nirvāṇa through personal effort | Eternal life through Christ |

| Afterlife | Rebirth & karma | Resurrection & divine judgment |

| Moral Authority | Karma & precepts | God’s commandments & grace |

Buddhism vs. Hinduism

Roots & Divergence

Origins: Buddhism arose from the Śramaṇa movement, distinct from Vedic/Brahmanical Hinduism.

Scriptures: Hinduism centers on the Vedas; Buddhism rejects them and relies on teachings attributed to the Buddha.

Soul (Ātman): Hinduism affirms an eternal soul; Buddhism teaches anattā (no permanent self).

Gods: Hinduism is polytheistic (or monistic); Buddhism includes gods within samsara but not as creators or saviors.

Liberation: Hinduism seeks moksha via devotion, knowledge, yoga; Buddhism seeks nirvāṇa through the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path.

In summary, Buddhism emerged as a reform movement rejecting hierarchical caste, Vedic ritual, and belief in eternal soul—offering a universal, ethical, and practice-based path to liberation.

The Most Sacred Buddhist Sites

Central to Buddhist pilgrimage are the “Four Great Places” tied to key moments in the Buddha’s life:

1. Lumbini (Nepal): The birthplace of Siddhārtha Gautama (c. 563 BCE), marked by the Maya Devi Temple and Ashoka’s pillar. A UNESCO World Heritage site, it draws global pilgrims.

2. Bodh Gaya (India): Where the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree. Home to the sacred tree, Mahabodhi Temple, and the Diamond Throne.

3. Sarnath (India): Location of the Buddha’s first teaching of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, also known as “Turning the Wheel of Dharma.”

4. Kushinagar (India): Where the Buddha entered final nirvāṇa (parinirvāṇa) and passed away in his 80s.

Beyond these primary sites, there are other major pilgrimage destinations:

- Sri Lanka’s Temple of the Tooth (Kandy): Housing a relic of the Buddha’s tooth.

- Myanmar’s Shwedagon Pagoda (Yangon): Revered stupa containing relics of four Buddhas.

- Tibet’s Jokhang Temple (Lhasa): The spiritual center and revered pilgrimage spot.

- Thailand’s Temples in Bangkok and Ayutthaya: Including Wat Pho and the Grand Palace.

- Botanical sacred sites like the Bodhi Tree descendant at Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.

These places form a ritual geography connecting practitioners physically and spiritually with foundational events in the Buddha’s life, reinforcing faith and devotion across Buddhist traditions.

Here are the draft sections for the Eightfold Path (theory and detailed explanation) and Buddhist Symbols & Meaning, with web-verified content and citations:

The Eightfold Path: Theory

The Noble Eightfold Path—Aṣṭāṅgika‑mārga in Sanskrit—is the fourth part of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths and describes the practical guide for ending suffering (dukkha). Positioned as the Middle Way, it avoids extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.

At its essence, the Path is structured around the Threefold Training:

- Wisdom (paññā): Right View, Right Intention

- Ethical Conduct (sīla): Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood

- Mental Discipline (samādhi): Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, Right Concentration.

Each factor supports the others, forming an integrated approach to personal transformation. The Buddha, in his first sermon (“Turning the Wheel of Dharma”), framed this path as that which “produces vision, produces knowledge” leading to peace, direct knowing, awakening, and liberation.

While often numbered, these elements are not sequential steps; rather, they are principles cultivated simultaneously, each reinforcing the others. Practitioners are encouraged to develop them in concert, according to their capacity.

This empowers the individual not only with ethical integrity and mental clarity, but with the wise understanding needed to uproot suffering at its source: ignorance of reality, craving, and attachment.

The Eight Paths Explained

Here’s an expanded breakdown of each of the eight elements:

1. Right View (Sammā‑diṭṭhi): Understanding the nature of suffering, its origins, cessation, and the path to liberation—the Four Noble Truths. Starts as intellectual insight, deepening through meditative realization.

2. Right Intention (Sammā‑saṅkappa) Developing intentions of renunciation, goodwill, and harmlessness, rooted in wisdom rather than attachment or aversion.

3. Right Speech (Sammā‑vācā): Communication based on truthfulness, kindness, non-harm, and avoiding gossip or idle chatter.

4. Right Action (Sammā‑kammanta): Behaving in ways that do not harm others: abstaining from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, and practicing moral virtue.

5. Right Livelihood (Sammā‑ājīva): Earning a living that does not cause harm—avoiding trades like arms, intoxicants, animal slaughter, or fraud—and preferably contributing positively to society.

6. Right Effort (Sammā‑vāyāma): Cultivating wholesome mental states and abandoning unwholesome ones—overcoming desire, ill will, ignorance, and cultivating mindfulness, motivation, and positivity.

7. Right Mindfulness (Sammā‑sati): Maintaining continuous awareness of body, feelings, mind, and mental phenomena—the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. This quality helps one observe mental processes without clinging or aversion.

8. Right Concentration (Sammā‑samādhi): Developing deep unified focus—samādhi—often via meditation on a single object like the breath. It stabilizes the mind, preparing it for insight into reality.

Buddhist Five Symbols & Meaning

Symbols offer visual embodiments of Buddhist teachings—both reminders and aids in meditation and ritual. Among the most central are:

Dharma Wheel (Dharmachakra): One of the earliest and most powerful symbols: a wheel with eight spokes representing the Eightfold Path. It also signifies the Buddha turning the wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon.

Lotus Flower: Emerging pristine from muddy waters, the lotus symbolizes purity, spiritual awakening, and the ability to transcend suffering.

Stupa: These dome-shaped structures house relics or sacred texts. Embodying the enlightened mind, they represent the five elements and symbolize the Buddha’s presence and attainment.

Bodhi Tree: Commemorates the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment in Bodh Gaya—often depicted in temple reliefs or standing branches.

Prayer Wheel: Especially in Tibetan traditions, spinning prayer wheels inscribed with mantras is equivalent to orally reciting prayers, amplifying merit.

The Eight Auspicious Symbols (Aṣṭamaṅgala)

A set of eight sacred icons frequently depicted on ritual objects and decorations:

- Golden Fishes – Freedom from suffering cycles

- Lotus – Purity and awakening

- Conch Shell – Proclamation of Dharma

- Victory Banner – Triumph over ignorance

- Treasure Vase – Abundance and health

- Parasol – Protection of beings

- Dharma Wheel – Path to enlightenment

- Endless Knot – Interconnectedness and timelessness

These symbols permeate Buddhist visual culture and serve as constant reminders of core principles—ethical discipline, mental clarity, and wisdom.

Major Buddhist Texts

Buddhist literature encompasses a vast and diverse canon, reflecting the evolution of different traditions—Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. These texts are foundational to practice and scholarship, offering discourses, teachings, and rituals central to each lineage.

🕮 Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) — The Theravāda Core

The Pāli Canon, also called the Tipiṭaka (“Three Baskets”), is the most ancient complete Buddhist canon, orally transmitted until it was written in Sri Lanka in the 1st century BCE. It comprises:

- Vinaya Piṭaka: Monastic code.

- Sutta Piṭaka: Sermons of the Buddha, including:

- Dhammapada: A concise compilation of ethical verses, recognized as “one of the most widely known Buddhist texts”.

- Mahāparinibbāna Sutta: An extensive discourse recounting the Buddha’s final days and parinirvāṇa.

- Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: The pivotal sermon that “sets the Wheel of Dharma in motion”.

- Abhidhamma Piṭaka: Scholastic treatises on phenomenology and psychology.

These three collections are recognized across traditions for their historical weight and direct link to the Buddha’s teachings.

Mahāyāna Sutras — Expanding Insight and Devotion

Mahāyāna traditions introduced a rich array of scriptures that build on early teachings with deep philosophical and devotional dimensions:

- Prajñāpāramitā Sutras (“Perfection of Wisdom”), such as the Diamond Sutra, emphasize the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena and are central to Mahāyāna philosophy.

- Lotus Sutra: Advocates the “One Vehicle” philosophy and inclusivity of all beings in attaining Buddhahood.

- Vimalakīrti Sutra: Highlights layperson enlightenment and non-duality in Mahāyāna thought.

- Pure Land Sutras: Grounding Pure Land devotion to Amitābha Buddha, promising rebirth in a blissful realm.

- Additional influential works include the Avataṃsaka Sutra, Lankāvatāra Sutra, and Mahāparinirvāṇa Sutra.

Tibetan Canon — Buddhist Texts & Commentaries

In Vajrayāna Buddhism, the Kangyur (“Translated Words” of the Buddha) and Tengyur (subsequent scholarly commentaries) form the complete Tibetan Canon. It comprises early sermons, tantras, and dense philosophical expositions. One notable text is Bhāvanākrama, a three-tier meditation guide by Kamalaśīla, which remains fundamental in Tibetan practice.

Canonical Integrity & Canonicity

All major traditions adhere to the Tripiṭaka structure—Vinaya, Sūtra, and Abhidharma—though their contents and emphasis vary. While Theravāda prioritizes the Pāli Tipiṭaka, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna preserve early texts alongside Mahāyāna sutras and commentaries. Scholars note that Mahāyāna schools regard early suttas authoritative, supplemented by their own evolving corpus.

Why These Texts Matter?

Dhammapada: A timeless guide for ethical living—concise, poetic, and accessible.

Diamond & Heart Sutras: Key resources in Mahāyāna philosophy exploring emptiness and awakening.

Lotus Sutra: Emphasizes universal potential for Buddhahood.

Bhāvanākrama: Offers step‑by‑step meditation training rooted in both theory and practice.

The Kangyur/Tengyur collection: Ensures Vajrayāna preserves tantric traditions and philosophical nuance.

Together, these texts empower practitioners across traditions—monastics, scholars, and laypersons alike—to engage in reflection, meditation, devotion, and wisdom.

Here’s the final section and conclusion, integrating modern relevance and psychology for a strong finish:

Modern Relevance & Conclusion

In our fast-paced, stress-heavy world, Buddhism’s ancient teachings are finding fresh relevance—especially through mindfulness, mental health, and ethical action.

Mindfulness in Healthcare & Psychology

The concept of mindfulness entered mainstream medicine thanks to Jon Kabat-Zinn, who developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in 1979. MBSR combines meditation, body scanning, and gentle yoga to help participants cope with anxiety, depression, pain, and stress. Kabat-Zinn’s approach sparked a wave of peer-reviewed research demonstrating benefits such as reduced cortisol, improved quality of life, decreased pain, and enhanced coping skills.

Clinical trials revealed that MBSR performs as well as antidepressants in relieving anxiety—but with significantly fewer side effects. Meta-analyses found “moderate effect sizes” for reducing stress, cultivating mindfulness, and boosting psychological well-being across a spectrum of individuals—from cancer patients to medical students.

However, debate continues around “McMindfulness”—criticisms that secular adaptations may dilute Buddhism’s ethical disciplines and spiritual foundations.

Engaged Buddhism & Ethical Activism

Emerging in the mid-20th century, Engaged Buddhism applies Buddhist values to real-world social issues—peacebuilding, environmental protection, human rights, and caste justice. Influenced by Vietnamese Zen master Thích Nhất Hạnh and Indian leader B. R. Ambedkar, it calls for compassionate action rooted in teachings such as the Middle Way and dependent origination.

Central to this movement is interbeing, a concept coined by Thích Nhất Hạnh, emphasizing interdependence and mutual responsibility. His Order of Interbeing actively advocates for mindfulness-based ethics, peace, and social justice in communities worldwide and continues to grow.

Buddhism in the Digital Era

Buddhism is also shaping conversations in technology, leadership, and innovation. Conferences like Wisdom 2.0 illustrate how mindfulness and compassion inform modern work culture, creativity, and responsible tech design. Popular apps like Headspace and Calm—built on Buddhist mindfulness—spark discussions about retaining integrity and context in digital practices.

Final Reflection

From its origins in the foothills of ancient India to its global influence today, Buddhism proves to be a timeless, living tradition. Its core frameworks—the Four Noble Truths and Noble Eightfold Path—remain deeply relevant, whether for personal insight or collective compassion.

While rooted in ancient texts like the Pāli Tipiṭaka, Mahāyāna sutras, and Tibetan commentaries, Buddhism continues evolving through modern applications: meditation in mental health treatment, ethical action in social justice, and mindfulness in the workplace.

The Dharma Wheel, Lotus, Stupa, and Order of Interbeing symbolically convey its principles, while pilgrimage sites like Bodh Gaya and Lumbini maintain spiritual continuity.

Ultimately, Buddhism offers more than spiritual solace—it offers a path to wisdom, peace, and liberation that resonates in our globalized, interconnected world. Whether embraced as a religious tradition or a secular philosophy, Buddhist practice invites us toward mindful, compassionate, and engaged living.

📚 Sources & References

Mindfulness & MBSR

Kabat‑Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Niazi, A. K., & Niazi, S. K. (2011). Mindfulness‑based stress reduction: A non‑pharmacological approach for chronic illnesses. North American Journal of Medical Sciences.

Landau, S. D., & Jones, F. W. (2021). Finding the spiritual in the secular: A meta‑analysis of changes in spirituality following secular mindfulness‑based programs. Mindfulness, 12(7), 1581–1595.

Proulx, J., Croff, R., & Oken, B. (2018). Considerations for Research and Development of Culturally Relevant Mindfulness Interventions in American Minority Communities. Mindfulness, 9, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0785-z

Groves, P. (2016). Mindfulness in psychiatry – where are we now? BJPsych Bulletin, 40(6), 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.115.052993

Kabat‑Zinn, J. (2005). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Clinical & Meta‑analytic Evidence

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness‑based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta‑analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., … Shanman, R. (2016). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta‑analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2

Fox, K. C. R., Dixon, M. L., Nijeboer, S., Girn, M., Lifshitz, M., Ellamil, M., … Christoff, K. (2016). Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta‑analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 65, 208–228. https://arxiv.org/abs/1603.06342

Secular Mindfulness Critiques

Farias, M., & Wikholm, C. (2016). Has the science of mindfulness lost its mind? BJPsych Bulletin, 40(6), 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.053686

Krznaric, R. (2017, May 26). How we ruined mindfulness. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/4792596/mindfulness-exercises-morality-carpe-diem/

Modern Applications & Engaged Buddhism

Reynolds, F. (2025, February). Mindfulness in psychiatry: A bridge to wellbeing for diverse communities. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved from APA website.

Li, J., Cochrane, K. A., & Leshed, G. (2024). Beyond Meditation: Understanding Everyday Mindfulness Practices and Technology Use Among Experienced Practitioners. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.10334

Lukoff, K., Lyngs, U., Gueorguieva, S., Dillman, E. S., Hiniker, A., & Munson, S. A. (2020). From ancient contemplative practice to the app store: Designing a digital container for mindfulness. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.09521

Media & News on Mindfulness

Krznaric, R. (2017, May 26). How we ruined mindfulness. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/4792596/mindfulness-exercises-morality-carpe-diem/

Remaley, K. (2014, January 23). The mindful revolution. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/1556/the-mindful-revolution/

Cendamo, L. (2023, May 5). Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn: Bringing mindfulness to the mainstream. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/jon-kabat-zinn-bringing-mindfulness-mainstream-7377237