Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction - Gladiator Life in Rome’s Colosseum

- 2 Where Did Roman Gladiator Fights?

- 3 Roman Gladiator Fights: Rules & Ritual ⚔️

- 4 Gladiators and the Colosseum

- 5 Gladiator Training 💪

- 6 Roman Gladiator Helmet

- 7 Common Types of Gladiators

- 8 Strategic Pairings of Roman Gladiator Fighters

- 9 Roman Gladiators: Social Status & Legacy

- 10 The Spectacle Beyond Combat

- 11 Modern Reinterpretations & Public Memory

- 12 Conclusion

- 13 📚 References

Introduction - Gladiator Life in Rome’s Colosseum

Ancient Rome’s Ancient Rome’s Roman gladiator Fights stand as some of history’s most iconic and enduring figures. These warriors—often slaves, prisoners of war, or volunteers stand as some of history’s most iconic and enduring figures. These warriors—often slaves, prisoners of war, or volunteers—captured the public’s imagination, stepping into grand arenas armed with swords, shields, and raw courage. Their battles weren’t mere skirmishes; they were Roman gladiator fights—the ultimate form of ancient entertainment, drawing roaring crowds craving adrenaline, spectacle, and martial valor.

A question that echoes through centuries is: Where did gladiators fight? While the image of the Colosseum looms largest in our minds, gladiators actually battled in a variety of venues throughout the Roman world—ranging from temporary wooden structures in the Forum and Circus Maximus to purpose-built amphitheaters dotted across the empire. Yet nothing compared to Rome’s Flavian Amphitheatre—more commonly known as the Colosseum—in scale, design, or cultural impact.

In this article, we’ll journey into the heart of these spectacles. We’ll explore the architecture of the Colosseum, answer where is the Colosseum?, and examine what life was like for a gladiator—from grueling gladiator training regimes to the protective artistry of the Roman gladiator helmet. We’ll also investigate the rich variety of types of gladiators, each with unique weapons and styles, and reflect on the cultural legacy of Roman gladiators long after the last triumphant roar faded.

Where Did Roman Gladiator Fights?

Gladiators didn’t confine their battles to the iconic Colosseum in Rome—they fought across the breadth of the Roman Empire in purpose-built venues known as amphitheaters. These oval or circular arenas were essential to Roman gladiator fights, and their spread underscores just how central gladiatorial combat was to Roman public life.

Origins & Evolution of Gladiatorial Combat

The origins of gladiatorial combat trace back to Etruscan funeral rites, where combatants fought as offerings to the dead—the earliest recorded event took place in 264 BCE. By the Republican era, Roman amphitheaters were constructed to host these spectacles in public ﹣ culminating in the development of grand structures across the empire.

Spread Across the Empire

At its height, Rome boasted approximately 230 amphitheaters in its territories, ranging from monumental stone edifices to humble wooden setups. Examples include:

- Rome’s Colosseum, begun in AD 72 by Emperor Vespasian and completed under his son Titus in AD 80.

- The Amphitheatre of Capua, near Naples—one of the earliest and largest gladiator arenas and the first known gladiator school.

- Arena of Nîmes (France), built around AD 70, seating up to 24,000 and hosting both gladiatorial bouts and wild animal hunts.

- The Amphitheatre of Italica near Seville, Spain, erected in AD 117–138 with a capacity of ~25,000.

- Amphitheatre of Mérida in Spain, dating to 8 BCE, designed for gladiatorial combat and beast fights.

- El Jem in Tunisia, built circa 238 AD with seating for ~35,000, now a UNESCO site.

In Britain, venues like those at Chester and Silchester (c. 50–70 AD) supported local games—including gladiator bouts—demonstrating the empire’s cultural reach.

Anatomy of an Amphitheater

Roman amphitheaters were carefully designed for spectacle and crowd control. They featured:

- An oval arena with tiered seating (cavea) arranged in sections for social stratification.

- A central sandy floor (arena) with subterranean passages (hypogeum) for staging combatants and animals.

- Entrance for spectators through multiple arcades, providing efficient access and exit.

These venues were not just arenas; they were complex public venues showcasing the political, military, and cultural might of Rome.

Roman Gladiator Fights: Rules & Ritual ⚔️

Gladiator combat might seem chaotic, but the truth is that these spectacles followed structured rules, overseen by referees, and were deeply ritualistic in nature.

Origins: From Munera to Mass Spectacles

Gladiator contests began as munera, funerary rites held in honor of the deceased. The earliest recorded event took place in 264 BCE, staged by the sons of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in the Roman Forum, using twenty-two pairs of fighters to honor their father. Over time, Roman gladiator fights shifted from solemn ceremonies to grand public spectacles, sponsored by politicians and emperors aiming to influence public opinion.

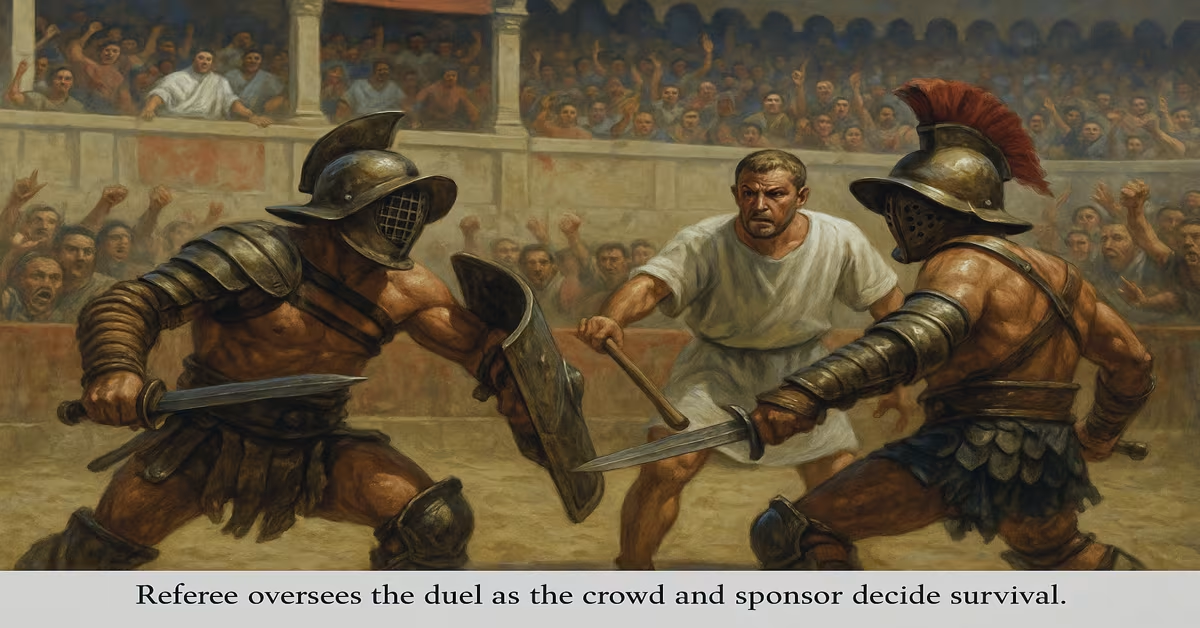

Referees: The Summa & Secunda Rudis

Combat was rigorously supervised by officials known as the summa rudis and secunda rudis, typically ex-gladiators, who wore white tunics with purple stripes and carried wooden staffs to enforce rules. Their responsibilities included:

- Starting and pausing bouts

- Intervening during mishaps (e.g., broken equipment) and calling diludium—a temporary break.

- Enforcing fair play and cautioning fighters.

- Administering punishment, such as whip lashes, for fighters who refused to engage.

- Declaring submission when a gladiator raised their finger (ad digitum).

A gladiator’s gravestone tells of Diodorus, who wrote, “Fate and the cunning treachery of the summa rudis killed me,” illustrating the referee’s powerful authority.

Submission, Mercy & the Crowd

Gladiators could surrender by raising a finger, requesting mercy (missio). The final decision lay with the event sponsor (editor), often influenced by audience reaction. Historians suggest only about 10–20% of fights resulted in fatalities, with some periods seeing even lower death rates. One modern estimate places early Imperial mortality around 15–20%, rising later to nearly 50%, though by the era of Emperor Augustus lethal fights (sine missione) were officially banned.

As one Reddit historian summarized: “Death was not the AIM of a given gladiatorial match … often ended with one combatant standing above the prone and exhausted (sometimes heavily injured, but still very much alive) body of an opponent”

Fighting in Rounds & Ritual Breaks

Matches were not a free-for-all—they unfolded in rounds. If combatants grew weary, the summa rudis could call a diludium, allowing respite and even medical treatment before the bout resumed. This structure emphasized stamina and strategy over sheer brute force, aligning gladiators with athletic rather than suicidal spirits. As one analysis put it:

“Gladiatorial fights had rules, including fighting in rounds. Referees were present to enforce rules, caution fouls, and handle appeals”

Spectacle & Political Theater

Beyond combat, gladiatorial bouts were theatrical events featuring music, processions, and drama. Trumpet fanfares, marching squads, and even occasionally flooded arenas (naumachiae) turned the amphitheater into a stage for power and performance. The referee and sponsor maintained this delicate balance, ensuring gladiators demonstrated courage, skill, and virtue—embodying Roman ideals of virtus—without unnecessary bloodshed.

Roman gladiator fights were highly ritualized events governed by:

- Historical roots in funerary munera

- Structured rules and referees (summa/secunda rudis)

- Submission gestures (ad digitum) and crowd involvement in mercy decisions

- Organized rounds and mandatory pauses (diludium)

- Dramatic spectacles reinforcing political and cultural values

Together, these elements crafted gladiatorial combat into a disciplined blend of athleticism, ritual, and political theater—not the free-for-all carnage often portrayed in modern media.

Gladiators and the Colosseum

The Colosseum—formally the Flavian Amphitheatre—is the architectural and cultural icon most associated with Roman gladiator fights. Built between AD 70–80 under Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, it revolutionized how Romans staged mass entertainment.

🏗️ Construction & Design

- Constructed on land that was once Nero’s Golden House lake, the Colosseum’s enduring site symbolizes imperial power used for public spectacle.

- The oval structure measured approximately 189 x 156 m and could hold around 50,000–80,000 spectators seated hierarchically across the cavea.

- Its architecture combined stone and concrete vaults in Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders—setting Renaissance standards for classical revival.

🎭 Events Beyond Swordplay

- For the inauguration in AD 80, Emperor Titus hosted 100 days of grand spectacles that included Roman gladiator fights, wild beast hunts (venationes), executions, and mock naval battles (naumachiae).

Venationes involved exotic animals like lions, bears, and elephants, sometimes in dangerous hunts against humans (bestiarii) or other animals.

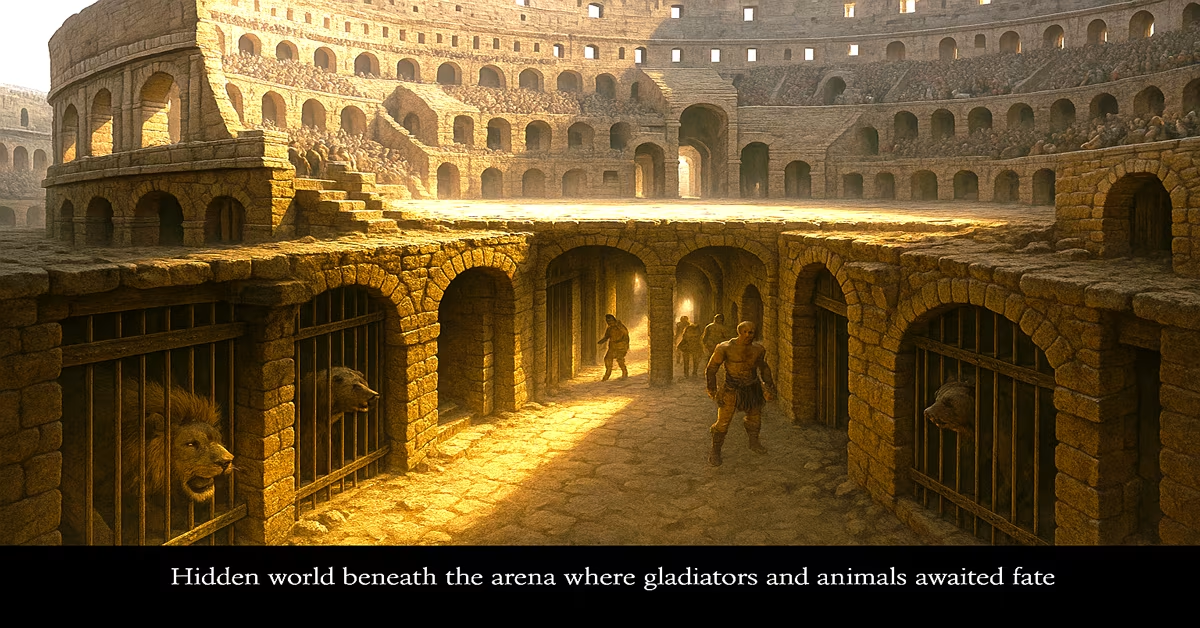

The Hypogeum & Stagecraft

- Beneath the arena floor lay the hypogeum: a complex network of tunnels, chambers, shafts, and elevators which facilitated surprise entrances of gladiators and animals.

- Domitian added this subterranean level after the initial opening to enhance theater production and logistics.

- A recent restoration has reopened these areas for guided tours, allowing visitors to traverse original corridors and elevator pits once used to transport combatants and beasts to the surface.

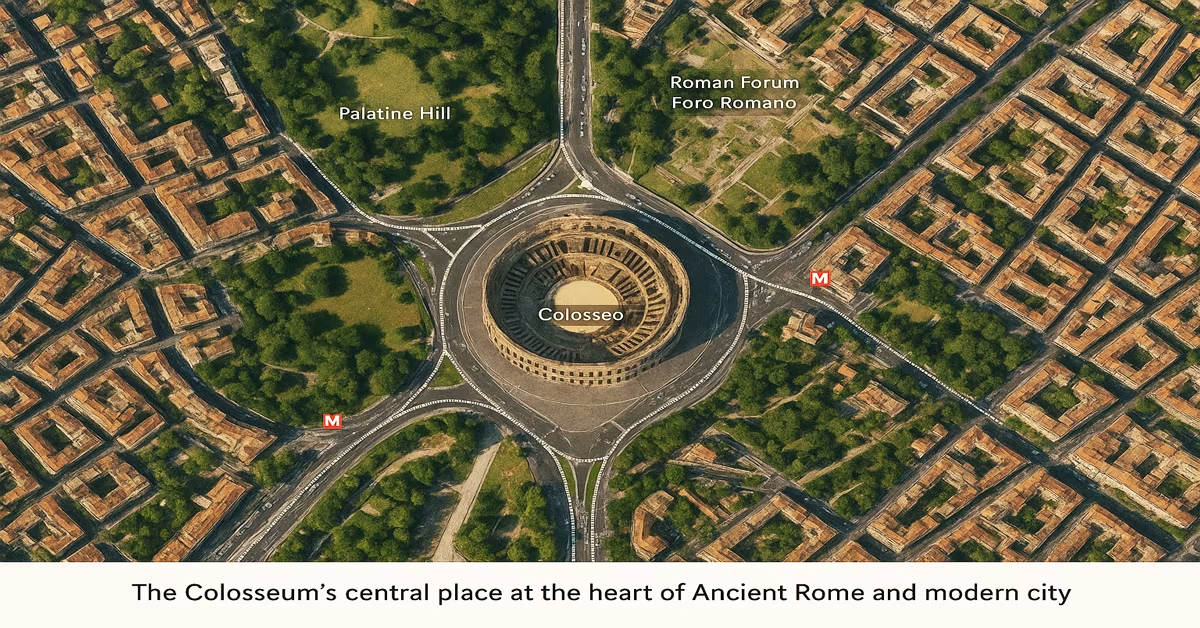

Where Is the Colosseum?

The Colosseum, formally the Flavian Amphitheatre, remains one of the most enduring symbols of Ancient Rome. Here’s everything you need to know about its location, access, and significance. Located at Piazza del Colosseo, 1, in central Rome—nestled between the Palatine and Esquiline Hills near the Roman Forum.

Address: Piazza del Colosseo, 1, 00184 Rome, Italy.

GPS Coordinates:

Approximately 41.8902° N latitude and 12.4922° E longitude.

Some sources provide slightly precise values like 41° 53′ 24″ N and 12° 29′ 33″ E. Easily accessible via Rome’s public transit: the Colosseo metro station on line B, numerous bus lines (e.g., 51, 75, 85), and tram lines 3 and 8.

Iconic Status

- The Colosseum sits at the edge of Regio III Isis et Serapis—a testament to the Flavian dynasty’s legacy and Roman urban planning.

- Its centrality and grand scale — the largest amphitheater ever built — underscore its ongoing role as the historical and cultural heart of Rome.

Restoration & Modern Experience

- Recently restored with funds from Italian fashion house Tod’s, work included cleaning the exterior façade and rehabilitating hypogeum areas—expanded public access by roughly 25%.

- The underground tunnels, once reserved solely for gladiators and staff, are now among the most popular aspects of Colosseum tours, heightening visitor appreciation of ancient staging and engineering.

The Colosseum stands as the ultimate crucible of Roman gladiator fights—an architectural marvel designed to entertain, intimidate, and showcase Rome’s might. Its grand awakening under Titus, subterranean hypogeum drama, and modern restoration efforts tell a dramatic story of cultural spectacle spanning millennia. In the next section, we’ll explore gladiator training that prepared fighters for this mighty arena.

Gladiator Training 💪

Gladiators underwent rigorous, highly structured training within specialized schools known as ludi, preparing them physically and psychologically for the arena.

Ludi & the Ludus Magnus

- Ludi gladiatorii were dedicated training schools where recruits lived, ate, and practiced daily. These “schools” also included armories, infirmaries, and public viewing areas for spectators.

- Rome’s most famous school, the Ludus Magnus, sat just east of the Colosseum, connected by an underground gallery. Built by Domitian (AD 81–96) and later renovated under Trajan, it housed and trained gladiators for the grand arena.

It featured a central ellyptical training arena (approx. 63 x 42 m), surrounded by seating for around 3,000 spectators—functioning as a micro-appearance before the main event.

🎯 Training Structure & Discipline

- Under the supervision of a lanista (owner-manager) and doctores (instructors, often former gladiators), trainees were grouped by fighting style and elevated through ranks—often achieving primus palus, the top grade in their class.

- Physical training started with wooden weapons and drills:

- Wooden swords (rudis) and heavy gear developed strength and technique, practiced against a wooden stake (palus) to simulate opponents.

- Docent instructors and senior gladiators (e.g. primus palus secutorum) demonstrated advanced techniques and disciplined the novices.

Diet & Medical Care of Gladiators

- Gladiators followed a high-carbohydrate, largely vegetarian diet known as sagina—earning them the nickname hordearii (“barley-eaters”). Diet staples included barley porridge, legumes, dried fruits, occasional cheese, and ash or bone-ash calcium supplements.

- This high-carb diet helped build a layer of fat for protection, contrary to modern “fit” ideals, but effective for their needs.

- Despite their harsh image, gladiators received surprisingly advanced medical attention. Physicians (like Galen in Pergamum) and masseurs treated injuries to ensure fighters remained fit and valuable, with low mortality during training.

Daily Routine & Psychological Conditioning

- Days began at dawn with physical conditioning, followed by combat drills, palus practice, and sparring sessions—heavy focus on endurance, agility, and mastery of the assigned weapon style.

- Training was punitive and psychologically intense. Infractions could lead to beatings, public humiliations, or worse—training also prepared gladiators mentally for death in the arena.

- “Mock battles” provided realistic simulation, while senior gladiators mentored newcomers, reinforcing hierarchy and technique.

Lives in Training Schools

Gladiators lived communally, sleeping in basic dormitories and eating together in mess halls (monomachotrophium), building camaraderie despite the constant threat of facing each other in combat.

Schools functioned like miniature prisons, managed strictly by the lanista, his staff of doctores, armourers, doctors, and attendants—ensuring control, performance, and profitability.

Financial & Social Dynamics

Gladiators were a significant investment. Lactucae schools could house hundreds of fighters, each costing a modern equivalent of $10,000–20,000 annually in food, medical care, and training—plus lucrative trainer and rental profits.

While primarily slaves or prisoners, some volunteers joined seeking fame, freedom, or ransom money—added diversity to the gladiatorial population.

Gladiator training was a disciplined blend of physical rigor, psychological endurance, specialized weapon practice, diet, and healthcare—all under the tight control of the ludus system. These warriors were forged not just to fight—but to survive, entertain, and captivate in the arenas of Ancient Rome.

Roman Gladiator Helmet

The Roman gladiator helmet (galea) was both a life-saving shield and a symbol of identity. Gladiators’ helmets were purpose-built for the arena—heavy, stylized, and tailored to each fighter’s style and opponent.

Style Meets Functionality

Murmillo Helmet: Crafted from bronze, this helmet featured a broad brim, grill-like visor, and crest resembling a fish—reflecting the Greek term mormylos, a fish species. The firm face grill provided protection, though it limited hearing and peripheral vision. The crest sometimes held horsehair or feathers, and parade versions were ornately decorated with mythological scenes—like the fall of Troy—carved on the bronze faceplate.

Thraex (Thracian) Helmet: A heavy bronze piece with full head coverage and a distinctive wide brim. It often included a hinged visor and eye slits, topped by a griffin crest—an homage to Nemesis, the goddess of retribution. Feather holders on the sides allowed for plume decoration.

Secutor Helmet: Tailored for duels with the agile retiarius, this helmet had a smooth, rounded surface and minimal ornamentation—featuring tiny eye-holes to guard against trident thrusts and nets. Its design reflected form meeting function—literally “pursuer” in Latin.

Other Types of Roman Gladiator:

-

- Hoplomachus helmets echoed Greek hoplite design with brims and cheek protection;

- Retiarius often fought bare-headed or wore open-faced, minimal helmets to aid mobility;

- The obscure andabata possibly fought blindfolded with no eye slits—though data remains speculative.

Materials & Weight of Roman Gladiator Helmet

These helmets were typically bronze, occasionally iron. They included internal padding, enhancing comfort and shock absorption, though even with this, they significantly restricted vision, hearing, and ventilation—requiring endurance and resilience. The murmillo helmet alone could weigh 2–4 kg, adding to the fighter’s physical burden.

Symbolism & Audience Recognition

Helmets were more than protection—they were visual shorthand. Each helmet signaled a gladiator’s type and anticipated fighting style, helping spectators instantly recognize who stood in the sands. Prestige fighters sported helmets with elaborate scene engravings or symbolic crests—like palm trees for victors or mythical creatures to inspire awe.

The Roman gladiator helmet was a masterpiece of craftsmanship and spectacle—offering protection, enhancing fighter identity, and playing a key role in audience engagement. Each helmet style aligned with the gladiator’s fighting class, performance requirement, and theatrical value in the arena. In the next section, we’ll dive deeper into the types of gladiators, including how the helmet factored into their distinct combat roles.

Common Types of Gladiators

Ancient Roman arenas featured a rich variety of gladiator classes, each defined by unique equipment, fighting styles, and symbolic meaning. These diverse combatants paired opponents strategically to create dramatic contrasts—heavy vs. light, sword vs. net, tradition vs. novelty—all designed to entertain and evoke themes of strength, survival, and spectacle.

1. Murmillo

- Heavily armored gladiator named after the fish-shaped crest on his helmet (mormyros in Greek) and wearing a large rectangular shield (scutum), a manica (arm guard), a greave, and a gladius (short sword).

- Their bulky equipment and disciplined style drew admiration as embodiments of Roman military strength.

2. Thraex (Thracian)

- Armed with a curved sword (sica), a small shield (parmula), and a griffin-crested helmet. Lightweight armor enabled agility and offensive tactics.

- Known for speed and cunning, the Thraex’s fighting style captivated spectators.

3. Secutor

The “chaser” specialized in battling the nimble Retiarius, wielding a gladius, heavy shield, manica, greave, and a streamlined helmet with narrow eye slits to deflect nets.

4. Retiarius

- Departing from conventional heavy armor, the Retiarius fought bareheaded, equipped only with a net, trident, dagger, arm guard, and shoulder guard.

- His tactics—casting nets, using reach advantage—created crowd-pleasing duels against heavier opponents.

Additional Gladiator Classes

Here’s a broader overview of other notable types:

- Samnite: Early gladiator styled after Samnite warriors, later replaced by Secutor.

- Provocator: Mid-weight gladiator with closed helmet, breastplate, sword, and shield, usually paired with another provocator .

- Dimachaerus: Dual wielding swords (dimachaeri), popular in the 2nd–4th centuries, varied armor.

- Hoplomachus: Inspired by Greek hoplites, fought with spear and small shield.

- Bestiarius & Venator: Not classic gladiators, but participated by engaging wild animals.

- Andabata: Wore closed helmets—possibly blindfolded—adding theatrical unpredictability .

- Cestus: Bare-knuckle or spiked glove fighters, rooted in Greek boxing tradition.

- Laquearius: The roper, wielding a lasso and secondary weapon.

- Gladiatrix: Rare female gladiators, seen as exotic novelties until banned in the 3rd century.

- Rudiarius: Free ex-gladiators, often carrying a wooden training sword to signify their status.

- Sagittarius: Horseback archers, usually pitted against condemned fighters.

- Cruppellarius: Heavily armored, akin to medieval knights.

- Scissor: Eastern novelty with unique weapons, primarily matched with Retiarius.

Strategic Pairings of Roman Gladiator Fighters

Roman matchmakers employed skillful contrasts to maximize drama:

Heavy vs. Light: Murmillo vs. Retiarius, showcasing strength vs. agility.

Cultural Clash: Thraex vs. Murmillo, blending exotic flair with disciplined force.

Mirror Mime: Provocator vs. Provocator, symmetrical battles of honor in armor.

Dual Dagger Duel: Dimachaerus fights emphasizing offensive dexterity.

Fan Insight from Reddit

One avid historian sums up this dynamic:

“The classes were trained to fight in certain pairings, … murmillo class originally represented the galic warrior, thrax was a thracian, hoplomachus was Greek hoplite, and scissor was added later by eastern empire and was also meant to fight retiarius.”

The varied types of gladiators were crucial for staging compelling Roman gladiator fights. Each class—whether heavily armored like the Murmillo, agile like the Retiarius, or exotic like the Gladiatrix—brought its own drama, tactics, and symbolism to the arena. This diversity kept crowds enthralled and underscored gladiatorial combat as both sport and performance art.

Roman Gladiators: Social Status & Legacy

Far from the faceless warriors we often imagine, Roman gladiators held complex social roles. Some were slaves, others volunteers, and a select few ascended to celebrity status—gaining freedom, luxury, and even influence.

Social Origins & the Status of Infames

Gladiators belonged to society’s fringes—either slaves, prisoners, or volunteers under contract (auctorati)—who renounced their legal standing and accepted punishments akin to slavery for a chance at glory or wealth. Even freeborn participants suffered infamia, losing rights like legal testimony or property claims (slavery in ancient Rome). Over time, many auctorati and successful performers secured improved status but remained legally tainted.

From Infames to Idols

Despite their official low rank, gladiators who excelled became icons. Mosaics, graffiti, pottery, and jewelry bear their likenesses. Spectators—especially women—cherished them: their sweat was collected and even used as cosmetics, while love notes hailed their allure . The Guardian reports the discovery of a gladiator-themed knife handle near Hadrian’s Wall—evidence that gladiator fame resonated across the empire.

Life Expectancy, Freedom & Wealth

Combat was perilous but not invariably lethal: early Imperial mortality stood around 20% per match, with only the tame gladiator fighting two to three times annually. Many won freedom after a few years—or on the spot—using a symbol of liberation, the wooden sword (rudis). Freed or highly decorated gladiators like Spiculus and Flamma received gifts, property, and even pensions. The arena’s top fighters were treated similar to modern sports icons, showered with money, admiration, and perks.

Influence on Culture & Politics

Gladiators shaped public life. Politicians and emperors—like Claudius and Nero—used the games for populist gain, leveraging popular fighters as symbols of power and imperial favor . Gladiators also appeared in literature, poetry, and monumental art. Historical accounts refer to them as sources of inspiration, shame, or moral debate—symbols of both strength and societal contradiction.

Decline & Lasting Legacy

Though condemned by early Christianity, gladiatorial games lasted over a millennium, ending around 404 CE under Emperor Honorius. Modern reenactments in venues from Tunis to Rome, and exhibitions at the Colosseum’s underground passages, celebrate their stories—highlighting skill over violence and cultural impact over bloodshed. From stadiums to museums, their legacy still fuels fascination.

The Spectacle Beyond Combat

The grandeur of the Colosseum went far beyond gladiatorial duels—these venues were stages for multifaceted spectacles, blending sport, theater, and political messaging to captivate Rome.

Morning: Venationes (Animal Hunts)

Roman amphitheaters hosted venationes, where exotic animals such as lions, tigers, elephants, and crocodiles were hunted by bestiarii or sometimes other gladiators. These events displayed Rome’s control over distant lands and provided visceral thrills through staged animal confrontations or executions (damnatio ad bestias) for entertainment and punishment.

From naumachiae, Roman amphitheaters recreated naval warfare. Initially staged in artificial basins, the Colosseum itself was flooded at least twice—during its inaugural games in AD 80 by Titus, and again under Domitian—to host scaled-down ships and reenact historic battles like Athens vs. Syracuse. While the logistics were immense, sources confirm flat-bottomed ships and exotic island settings were used.

These spectacles were engineering marvels, draining and flooding the arena often within hours thanks to aqueduct and basin systems (hypogeum)—testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Midday: Public Executions & Mythological Dramas

Loitering condemned individuals might face gruesome midday pitfalls, through forced animal combat or dramatized death scenes based on mythological narratives. These horrific displays served as punishment and spectacle, amplifying political control and moral messaging about crime and virtue.

Political Theater & Civic Messaging

These games functioned as calculated political theater. Emperors and magistrates funded these spectacles to curry public favor, projecting strength, generosity, and divine association. The seating hierarchy itself showcased Rome’s social order—elite near the action, lower classes further up—reinforcing civic structure through architectural staging.

🌀 Full-Day Event Format

Typical festival days in venues like the Colosseum featured three acts:

- Morning: Venationes with exotic beasts

- Midday: Executions or myth reenactments

- Afternoon: Roman gladiator fights

Occasional naumachiae elevated the day to showpiece status. These all-day events were free to attend, crossing class lines and offering immersive civic experience.

Modern Reinterpretations & Public Memory

Gladiatorial spectacles persist today—not in blood—but in education, entertainment, and cultural remembrance. These modern echoes offer insight into ancient Rome while reshaping societal perceptions of the gladiators.

Guided Underground Tours

In 2010, the Colosseum’s subterranean chambers—once exclusive backstage areas for gladiators and animals—were opened to the public after extensive renovations funded by fashion house Tod’s. Now, visitors can traverse the dimly lit hypogeum, explore original corridors, platforms, and cages, and visualize gladiators staging for combat. These immersive experiences place the ancient arena into a modern context, offering parallels with today’s stadiums—structured entrances, tiered seating, and layered media arrangements.

Historically-Informed Reenactments

From Tunis to Rome and other amphitheaters across the Mediterranean, groups like Gruppo Storico Romano and Ars Dimicandi stage historically informed gladiator reruns, showcasing realistic weaponry, armor, and conduct. These performances emphasize authenticity over death—blunted blades, choreographed dueling, and staged results—highlighting that ancient matches were not always lethal.

Festivals, Workshops & Educational Outreach

Cultural initiatives led by the archaeological park of the Colosseum introduce reenactments, exhibitions, and educational workshops. They bring gladiator culture into living history curricula, especially for children, while major cities like Nîmes host annual spectacles in ancient arenas. These programs deepen public understanding, contextualizing gladiators as athletes and performers rather than mere violence icons.

Societal Reflection & Entertainment Parallels

Modern excursions, like gladiator training schools in Rome, demonstrate the allure of embodied experience. While participants feel a physical connection to the past, they also engage in a form of performance akin to WWE meets HEMA—blending athleticism, theatricality, and historical recreation . These experiences raise important questions:

- How much dramatization is acceptable before history becomes spectacle?

- Are these reenactments accurate reflections or modern adaptations of antiquity?

Rewriting the Myth & Legacy

Contemporary reinterpretations actively challenge myths—such as gladiators dying in every fight or the infamous “thumbs‑down” death sentence. Archaeological and textual evidence shows fights were often stopped early to save valuable fighters, and thumbs-down likely gained misleading Hollywood status. Today’s reinterpretations correct misconceptions and reshape public memory toward nuance, emphasizing skill, economics, and ritual over raw brutality.

Modern engagement with the gladiatorial world takes many forms—from the Colosseum’s underground tours and live reenactments to gladiator workshops and scholarly debates. These efforts frame gladiators as complex figures—trained athletes, entertainers, and agents within changing social, political, and cultural systems. In bridging ancient and contemporary worlds, they prompt us to reflect on violence, spectacle, and human agency.

Conclusion

The saga of the Roman gladiators—from their humble origins in funeral rites to becoming iconic athletes and entertainers—reveals much about Ancient Rome’s values, social systems, and politics. Their careers intertwined iconic instruments like the Roman gladiator helmet, strenuous gladiator training, and faction-specific types of gladiators within monumental venues like the Colosseum—the very place where did gladiators fight? It was here, at Piazza del Colosseo, that their skill, bravery, and drama played out for an empire.

But beyond fierce combat, gladiatorial spectacles were strategic tools. They served economic, political, and cultural purposes—from supporting local economies and urban infrastructure to reinforcing imperial authority through “bread and circuses” and orchestrated civic unity.

In modern times, their legacy endures in powerful cultural echoes:

- Architecture and stadium design: Contemporary arenas inherit the Colosseum’s elliptical plans, tiered seating, and crowd flow designs.

- Entertainment and sport: Today’s MMA, professional wrestling, action cinema, and even reality competitions reflect the gladiator spirit—structured combat, heroic narratives, and mass appeal.

- Myth vs. Reality: Modern reenactments, educational tours—like those unveiling the Colosseum’s hypogeum—seek to demystify popular misconceptions: that gladiatorial combat was excessively lethal, or that gestures like “thumbs-down” held historical accuracy, which turns out to be a Hollywood exaggeration.

Ultimately, gladiators remain emblematic of a broader human fascination with conflict, spectacle, and resilience. Their story encourages critical reflection: how do we reconcile brutality with entertainment, and what does it reveal about our relationship with violence and heroism?

From the sands of the arena to the digital fights of today’s screens, gladiators continue to matter—not just as relics, but as mirrors reflecting society’s enduring values. As we revisit their world, we honor their strength and learn from their paradoxes.

📚 References

Ancient Sources & Scholarship

- Civilization Chronicles. (n.d.). Exploring the Social Impacts of Gladiators in Ancient Rome. Retrieved from Civilization Chronicles website (civilizationchronicles.com)

- Men of Pompeii. (n.d.). The Evolution of Gladiatorial Games from Rituals to Spectacles. Retrieved from Men of Pompeii website (menofpompeii.com)

- Ancient Civs. (n.d.). The Enduring Legacy of Roman Gladiators in Ancient History. Retrieved from Ancient Civs website (ancientcivs.blog)

- Bookey app. (n.d.). The Gladiators – Chapter 5: Economic and Political Implications. Retrieved from Bookey website (bookey.app)

Diet & Physiology of Gladiators

- Grossschmidt, K., & Kanz, F. (2008, November). The Gladiator Diet. Archaeology Magazine, 61(6). Archaeological Institute of America.

- Kaiser, O., & Grossschmidt, K. (2007). Roman Gladiators—The osseous evidence. Paper presented at the Seventy-Sixth Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.

- Kanz, F., Grossschmidt, K., Risser, D. U., Moghaddam, N., & Lösch, S. (2014, October 15). Stable isotope and trace element studies on gladiators and contemporary Romans from Ephesus (Turkey, 2nd and 3rd Ct. AD)—Implications for differences in diet. PLOS ONE.

- Longo, U. G., Spiezia, F., Maffulli, N., & Denaro, V. (2008, 1 December). The best athletes in Ancient Rome were vegetarian! Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 7(4), 565.

- Mason, P. (2014, October 27). Roman gladiators knew the value of calcium. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 293(7836).

- National Geographic. (n.d.). Dinner with the gladiators: Beans and ashes. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/dinner-with-the-gladiators-beans-and-ashes

- BBC News. (2014, October 30). Gladiators were ‘mostly vegetarian’. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/education-29723384

- ScienceDaily. (2014, October 20). Roman gladiators ate a mostly vegetarian diet and drank a tonic of ashes after training. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/10/141020090006.htm

- Ngo, R. (2024, April 30). What did gladiators eat? Bible History Daily. Retrieved from https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/daily-life-and-practice/what-did-gladiators-eat/

Colosseum Architecture & Public Access

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.-a). How was the Roman Colosseum built? Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/technology/How-Was-the-Roman-Colosseum-Built

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.-b). Who built the Colosseum? Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/question/Who-built-the-Colosseum

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.-c). Titus [Profile]. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Titus

- Britannica Kids. (n.d.). Colosseum – Students. Retrieved from https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Colosseum/574423

- Wikipedia. (2025, June). Colosseum. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

- Condé Nast Traveler. (2017, March 28). You can now explore the Roman Colosseum at night. Retrieved from https://www.cntraveler.com/story/you-can-now-explore-the-roman-colosseum-at-night

Helmet, Classes & Social Themes

- The Collector. (2023). Gladiator helmets: 6 types and their characteristics. Retrieved from https://www.thecollector.com/gladiator-helmets-types-characteristics/

- Warriors & Legends. (n.d.). List of gladiator classes. Retrieved from https://www.warriorsandlegends.com/gladiators/list-of-gladiator-classes/

- Roman-Empire.net. (n.d.). Every Roman gladiator class explained. Retrieved from https://roman-empire.net/people/every-roman-gladiator-class-explained

Modern Interpretation & Tours

- Traveller’s Times. (2024). From Tunis to the Tiber, the new generation of gladiators. The Times.

- Condé Nast Traveler. (n.d.). A look inside the Colosseum’s long-hidden gladiator tunnels. Retrieved from https://www.cntraveler.com/story/rome-colosseums-newly-opened-underground-gladiator-tunnels

Additional Scholarly & Historical Context

- Penelope. (n.d.). The Roman Gladiator. Encyclopaedia Romana. Retrieved from https://penelope.uchicago.edu/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/gladiators.html

- Roth, L. M. (1993). Understanding architecture: Its elements, history, and meaning. Westview Press.

- Pliny the Elder. (n.d.). Naturalis historia.

- Follain, J. (2002, December 15). The dying game: How did the gladiators really live? Times Online.