Table of Contents

- 1 Jus sanguinis a citizenship rule

- 2 🌍 Global Implementation & blood-line citizenship policy overview

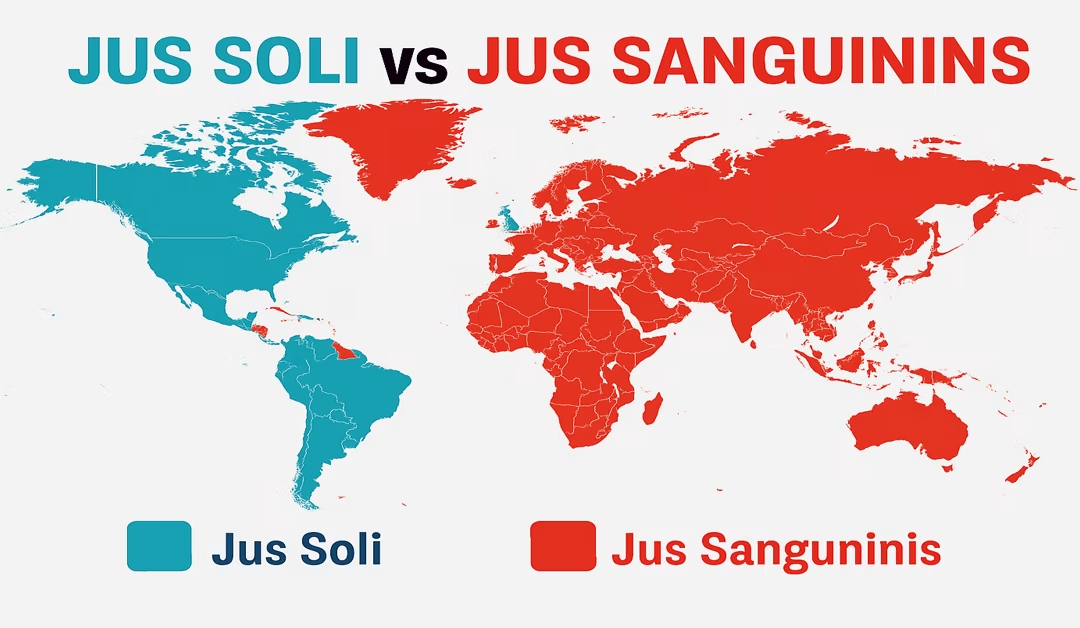

- 3 What is Jus Soli?

- 4 🌍 List of Countries with Jus Soli Citizenship Laws

- 5 Global Implementation & Policy Variations

- 6 Jus Sanguinis vs. Jus Soli: Comparative Analysis

- 7 👍 4. Advantages of Jus Sanguinis

- 8 Descent Citizenship Challenges

- 9 ✅ Case Studies of Jus Sanguinis in Action

- 10 International Law & Human Rights Norms

- 11 Real-World Case Studies: How Jus Sanguinis Plays Out

- 12 📚 References

Jus sanguinis a citizenship rule

Definition & Etymology: Jus sanguinis (Latin: “right of blood”) is a citizenship rule where nationality is granted based on descent from citizen parents, regardless of birthplace. According to Merriam-Webster, it means “a rule that a child’s citizenship is determined by its parents’ citizenship”. The European Migration Network defines “ius sanguinis” as nationality based on parents’ citizenship at birth or acquisition time.

Historical Evolution

Emerging from Roman and early modern continental legal traditions, jus sanguinis persisted in countries like Germany, Italy, and France into the 19th century. The 1860 codification of “jus soli versus jus sanguinis” marked a shift: European civil-law systems emphasized parentage, while British-origin jurisdictions stressed birthplace — a debate crystallized in the late 1800s by legal scholar Charles Demolombe.

The contrast was evident in the Franco-German 19th-century discourse: Fichte championed “blood-based nationality,” while Renan promoted civic territorial ties, leading to divergent national policies.

Modern Hybridity

Today, most states implement mixed nationality systems—combining jus sanguinis and jus soli. It’s rare for countries to rely solely on descent; many incorporate safeguards like ancestor generation limits and gender equality clauses.

🌍 Global Implementation & blood-line citizenship policy overview

Parentage Rules & Generational Limits

Countries around the world apply jus sanguinis in vastly different ways, particularly in terms of how descent can be passed from parent to child:

Unlimited Descent (Generationally Open)

Italy has long exemplified unrestricted descent-based citizenship. Under its 1912 law (as amended), Italian nationality may be passed down indefinitely—so long as each ancestor remained an Italian citizen at the time of their child’s birth. This expansive model grants eligibility to multiple generations of descendants without limitation.

Generational Cap (Limited Descent)

Canada, by contrast, enforces a strict “first-generation limit.” Children born abroad to Canadian citizens who themselves were born abroad do not automatically receive citizenship under normal circumstances. For example, a Canadian parent born in Canada may pass citizenship to a child born overseas, but if that child also spends their life abroad and has children abroad, those grandchildren do not automatically qualify—unless the parent lived in Canada for at least 1,095 days (about three years) before the child’s birth, under the proposed Bill C‑3.

Registration Condition (Deadline-Based Retention)

Germany operates under what could be described as “conditional descent.” Children born abroad to German parents hold German nationality only if the birth is formally registered at a German embassy or civil registry office before their first birthday—otherwise the entitlement is lost. This rule safeguards lineage while also imposing a precise administrative responsibility.

What is Jus Soli?

It is a Latin word for “right of the soil” Jus soli is a principle of nationality law under which a person’s citizenship is determined by the place where they were born — that is, by territorial birthright.

- If you are born on the territory of a country that follows jus soli, you automatically become a citizen of that country, regardless of your parents’ citizenship.

- This is sometimes called birthright citizenship.

➡️ Examples

- United States: Under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, anyone born on U.S. soil (with limited exceptions like children of foreign diplomats) is automatically a U.S. citizen.

- Canada & Mexico: Also have strong jus soli laws.

- Many countries in the Americas follow jus soli to encourage integration and equal rights for all children born there.

Summary of the Difference Jus Soli And Jus Sanguinis

|

Principle |

Meaning |

Citizenship based on |

Example countries |

|

Jus Soli |

“Right of the soil” |

Place of birth |

USA, Canada, Mexico |

|

Jus Sanguinis |

“Right of blood” |

Citizenship of parents |

Italy, Germany, Japan |

✅ Why us soli and Jus Sanguinis matters?

These two principles are at the core of global nationality laws, shaping who is considered a citizen, how diasporas keep ties to homelands, and how countries avoid problems like statelessness. Many nations today use a mix of both principles, balancing local integration (jus soli) with heritage and family ties (jus sanguinis).

🌍 List of Countries with Jus Soli Citizenship Laws

| 🇺🇸 United States | 🇨🇱 Chile | 🇵🇪 Peru |

| 🇨🇦 Canada | 🇺🇾 Uruguay | 🇧🇴 Bolivia |

| 🇲🇽 Mexico | 🇵🇾 Paraguay | 🇭🇳 Honduras |

| 🇦🇷 Argentina | 🇻🇪 Venezuela | 🇸🇻 El Salvador |

| 🇧🇷 Brazil | 🇪🇨 Ecuador | 🇬🇹 Guatemala |

| 🇳🇮 Nicaragua | 🇵🇦 Panama | 🇯🇲 Jamaica |

| 🇧🇧 Barbados | 🇹🇹 Trinidad and Tobago |

(Note: almost all of Latin America practices broad jus soli — it’s a regional norm often tied to post-colonial integration policies.)

⚠️ Countries with restricted or conditional jus soli

(Children born on the territory only acquire citizenship if certain conditions are met, e.g. parents are legal residents or not “in transit”)

- 🇦🇺 Australia (citizenship by birth if at least one parent is a permanent resident or citizen)

- 🇳🇿 New Zealand (similar conditional birthright rules)

- 🇮🇳 India (until 2004 was pure jus soli, now requires at least one parent to be an Indian citizen or legal resident)

- 🇬🇧 United Kingdom (since 1983, birth on soil only grants citizenship if at least one parent is a citizen or settled resident)

- 🇮🇪 Ireland (changed in 2005 to require Irish or resident parent)

- 🇿🇦 South Africa (must meet conditions if parents are not citizens)

- 🇫🇷 France (child born in France to foreign parents can acquire citizenship later under certain residence conditions)

📝 Important notes

- Many countries combine jus soli and jus sanguinis, with jus soli either unconditional (like the U.S. and Canada) or conditional (like Australia or the U.K.).

- The broadest unconditional jus soli regimes are primarily found in the Americas.

In Europe, Africa, and Asia, jus soli is usually restricted or supplemented with descent rules to control automatic citizenship grants.

Global Implementation & Policy Variations

Parentage Rules & Generational Limits

Countries around the world apply jus sanguinis in vastly different ways, particularly in terms of how descent can be passed from parent to child:

- Unlimited Descent (Generationally Open)

Italy has long exemplified unrestricted descent-based citizenship. Under its 1912 law (as amended), Italian nationality may be passed down indefinitely—so long as each ancestor remained an Italian citizen at the time of their child’s birth. This expansive model grants eligibility to multiple generations of descendants without limitation. - Generational Cap (Limited Descent)

Canada, by contrast, enforces a strict “first-generation limit.” Children born abroad to Canadian citizens who themselves were born abroad do not automatically receive citizenship under normal circumstances. For example, a Canadian parent born in Canada may pass citizenship to a child born overseas, but if that child also spends their life abroad and has children abroad, those grandchildren do not automatically qualify—unless the parent lived in Canada for at least 1,095 days (about three years) before the child’s birth, under the proposed Bill C‑3. - Registration Condition (Deadline-Based Retention)

Germany operates under what could be described as “conditional descent.” Children born abroad to German parents hold German nationality only if the birth is formally registered at a German embassy or civil registry office before their first birthday—otherwise the entitlement is lost. This rule safeguards lineage while also imposing a precise administrative responsibility.

Gender-Based Transmission

Historically, descent laws often favored patrilineal bloodlines, where only father’s nationality determined a child’s citizenship:

- Italy: Before 1948, an Italian mother could not pass her citizenship to her child. Marrying a foreigner often resulted in her losing Italian nationality altogether; children born to Italian mothers and foreign fathers were not granted citizenship.

- Even today, 24 countries continue to include some form of maternal descent limitation—with citizenship not consistently transmitted from the mother, potentially leading to statelessness.

Reforms underway:

- Many nations have amended citizenship laws to allow gender-neutral transmission, in line with global gender-equality standards advocated by organizations like the UN’s CEDAW.

In Germany, the law now permits maternal descent on equal terms with paternal descent, though previous generations had to contend with male-line preference.

Statelessness Safeguards

Strict adherence to jus sanguinis—without accompanying protections—can result in stateless children, especially when both parents are foreign-born in restrictive systems.

International frameworks have stepped in to address this:

- UN Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (1961)

This treaty requires contracting states to grant nationality to: - Children born in the country who would otherwise be stateless.

- Children born abroad to at least one national parent—if they would otherwise remain stateless.

- Foundlings discovered within the state’s territory.

Specifically, Article 4 mandates descent-based citizenship if it prevents statelessness, and Article 2 ensures foundlings acquire national status by default.

- Implementation in National Laws

To align with UN requirements, many countries have:

- Adopted conditional jus soli: grant citizenship if a child born locally would otherwise be stateless.

- Included foundling provisions: treating abandoned infants as nationals based on the state where they were found.

- Example: Germany offers jus sanguinis plus protections for children who would otherwise remain stateless, meeting international obligations.

Canada confirms citizenship for abandoned children found before age seven, treating them as if born in Canada unless proven otherwise.

Jus Sanguinis vs. Jus Soli: Comparative Analysis

|

Criterion |

Jus Sanguinis (Descent) |

Jus Soli (Birthplace) |

|

Basis |

Citizenship through parentage |

Citizenship through birth on national soil |

|

Inclusiveness |

Bloodline-limited; can exclude locals |

Broad; territory-based; includes all born there |

|

Statelessness Risk |

High without safeguards |

Lower overall; conditional exceptions apply |

|

Cultural Continuity |

Supports diaspora identity |

Encourages local civic identity |

|

Administrative Burden |

Complex rules, generational tracking |

Simpler—usually birth certificate suffices |

🇺🇸 United States

- Unrestricted Jus Soli

The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, ensures that anyone born on U.S. soil is automatically a citizen, regardless of their parents’ legal status—a principle supported as recently as January 2025 when President Trump’s executive order attempting to limit birthright citizenship was legally challenged. Federal judges have blocked nationwide enforcement, citing constitutional grounds, and legal experts deem efforts to undermine this guarantee unconstitutional. - Conditional Jus Sanguinis

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 specifies that children born abroad to at least one U.S. citizen parent may acquire citizenship, provided their parent has lived in the U.S. for a specified period before the child’s birth. This illustrates how descent-based citizenship is granted on a case-by-case basis, distinct from the automatic birthright on U.S. soil.

🇩🇪 Germany

- Descent with Registration Requirement

German nationality law automatically extends citizenship to children born abroad to at least one German parent. However, this entitlement must be confirmed by registering the child’s birth at a German embassy or consulate within one year. Failure to register results in loss of citizenship rights, a rule designed to maintain a clear connection to Germany, but which also places a burden on expatriate families.

🇮🇹 Italy

- Traditional Unlimited Jus Sanguinis

Historically, Italy allowed descendants of Italian-born citizens to claim nationality indefinitely, even through great-grandparents, provided there was an uninterrupted citizenship lineage dating from March 17, 1861. - 2025 Generational Reform

On March 28, 2025, Italy passed Decree-Law No. 36, later confirmed as Law No. 74/2025. It now limits descent-based citizenship to two generations: you must have a parent or grandparent born in Italy to qualify for citizenship by descent. Children whose Italian parent gained citizenship through descent abroad must also have that parent reside in Italy for at least two consecutive years before the child’s birth. - Transitional Measures

Pending applications submitted before March 27, 2025, and appointments booked by that date, remain valid under the prior rules. A referendum is also underway to reduce naturalization residency requirements from ten to five years.

🇮🇳 India

- Phasing out Unconditional Jus Soli

Up until 2004, India adhered to unconditional jus soli, granting citizenship solely upon birth in the territory. However, due to concerns over illegal immigration, the Constitution was amended to require at least one parent be an Indian citizen or a legal resident for ten years before the child’s birth. - Continued Jus Sanguinis with Conditions

Children born abroad to Indian citizen parents remain eligible for citizenship, but only if they are registered at an Indian consulate within a set time after birth, in line with the Citizenship Act and subsequent regulations.

✅ Takeaway – Country Examples Section

- U.S. combines unrestricted jus soli (14th Amendment) and restricted jus sanguinis (Child Citizenship Act), with recent executive attempts to limit birthright citizenship failing in court.

- Germany grants descent-based citizenship only if formal registration occurs within one year of birth abroad.

- Italy long allowed unlimited descent, but from March 2025, restricts rights to only two ancestral generations, with transitional protections.

India removed unconditional jus soli in 2004 and now pairs jus sanguinis with strict overseas registration rules for citizenship transmission.

👍 4. Advantages of Jus Sanguinis

Strengthening Diaspora Ties & Cultural Identity

Descent-based nationality laws help sustain connections between citizens and their diasporas by reinforcing shared heritage and identity.

- Cultural Continuity: When citizenship is passed through bloodlines, descendants of emigrants maintain legal links to their ancestral homeland, enhancing cultural preservation across generations. For example, Greek nationality law grants citizenship to children born abroad to Greek citizens and even descendants of ethnic Greeks whose grandparents were born in Greece, underscoring the importance of preserving national identity abroad.

- Diaspora Engagement: Citizenship by descent allows the diaspora to stay actively involved—through voting rights, dual citizenship, consular protection, and cultural participation. As one Redditor noted about Europe’s descent-friendly policies, “allowing jus sanguinis citizenship is a way for a country to benefit economically from its diaspora… who will generally have great sympathy for or enthusiasm about their ‘second country’”.

Safeguarding Against Statelessness

Granting citizenship by descent automatically provides children with nationality when at least one parent is a citizen, helping to fulfill international commitments to end statelessness.

International Law Compliance: Article 4 of the Council of Europe’s 1997 Recommendation emphasizes that jus sanguinis plays a crucial protective role: “The acquisition of the nationality of one of the parents at birth… should be automatic and not made conditional upon a registration or option, the absence of which would make them stateless” .

Effective Prevention: In many countries, descent-based citizenship ensures stateless children born abroad are automatically included under a parent’s nationality, reducing risks of statelessness—evidenced by international-humanitarian agencies like Refworld citing this benefit.

Streamlining Legal Processes

Jus sanguinis often simplifies nationality acquisition, bypassing residency, language requirements, or other hurdles inherent to naturalization systems.

Minimal Bureaucratic Burden: Descendants typically only need to prove lineage—via birth certificates, family registers, or sworn documentation—rather than long residency, tested integration, or civic examinations.

Administrative Efficiency: Multiple European countries (e.g., Italy, Greece, Japan) provide a straightforward legal path for automatic citizenship through birth-to-a-national parent, aligning citizenship more closely with identity than immigration bureaucracy.

National Ethnic Cohesion

Countries that prioritize a shared heritage apply jus sanguinis to preserve ethnic or cultural homogeneity, strengthening a sense of communal belonging.

- Cultural Homogeneity: Nations like Japan base nationality strictly on descent—children born abroad to at least one Japanese parent automatically receive nationality—and social attitudes continue to place greater emphasis on ethnic purity and national unity.

- National Unity: Similarly, Greece enables citizenship for people of Greek descent, even across generations, reinforcing a pan-diasporic ethnic identity. Its laws support multiple generations of ethnic Greeks abroad as full citizens, emphasizing shared roots and collective identity across borders.

Descent Citizenship Challenges

Complex Legal Structures

Descent-based citizenship systems are frequently tangled in multi-layered regulations—defining who qualifies, how deeply ancestry may be traced, what deadlines apply, and what documentation is required. These variations lead to administrative overload and legal missteps:

- Italy’s Generational Limits: Until 2025, Italian citizenship could be claimed by anyone with an ancestor alive after March 17, 1861. The new Decree-Law No. 36/2025 radically alters this, restricting eligibility to those with a parent or grandparent born in Italy. Applicants beyond that lineage must additionally demonstrate that their parent resided in Italy for at least two consecutive years before their birth—requirements that are legally complicated and retroactively enforced.

- Germany’s Registration Deadline: German children born abroad lose their entitlement if their birth isn’t registered with a German embassy within a year—an administrative timeline that’s easy to miss and difficult to contest once expired.

Such shifting rules and retroactive enforcement create legal confusion, long waits, and often leave eligible candidates without recourse or clarity.

Increased Statelessness Risk

Strict descent laws—especially those with parental or lineage limitations—may inadvertently produce stateless children:

Without clear maternal transmission or missed consular registration, children may be stripped of nationality, especially in states where both descent lines must be recognized equally or risk being overlooked.

Scholar exams underscore how gender-biased laws (see next section) often contribute to nationality gaps in children born abroad, increasing the likelihood of statelessness.

Exclusion of Long-Term Residents

Descent-oriented frameworks can leave behind many who were born or raised in a country but whose parents remained non-citizens:

- In Italy, even children proficient in the language and culturally Italian must wait until age 18 and meet strong residency criteria to naturalize. Meanwhile, distant descendants overseas may acquire citizenship easily—prompting strong critiques for fostering “second-class” residents with fewer rights ([FT]).

These restrictive naturalization regimes perpetuate inequality and fuel debates over fairness and identity.

Gender Bias

Historically, many nations favored patrilineal descent—granting nationality through fathers but not through mothers:

Italy’s pre-1948 laws barred women from transmitting citizenship, and 24 countries worldwide still hold legacy laws that restrict nationality transmission through mothers, creating a tiered system where identical children may be treated differently based solely on their parent’s gender.

Such biases have been legally challenged; for instance, Mexico and Argentina amended laws to correct these inequalities, aligning with CEDAW requirements. However, the slower pace of reform in many countries continues to perpetuate gender discrimination and nationality gaps.

Administrative & Political Pressures

Generous jus sanguinis laws can overwhelm bureaucracies and fuel political backlash:

Italy experienced a 40 % increase in citizens registered abroad—from 4.6 million to 6.4 million between 2014 and 2024. This surge mainly stemmed from distant descendants seeking passports for travel or economic benefits, prompting consular overload and rapid legal reform.

Municipal offices and courts have struggled to process paperwork—a Redditor described how awaiting transcription of birth certificates in Venice stretched beyond legal deadlines of six months, sometimes taking over a year in practice.

Politically, such surges trigger debates over resource allocation, national identity, and fairness—evident in Italy’s 2025 referendum and broader electoral discourse.

Ethical Concerns: The “Birth Lottery”

Assigning citizenship based on ancestry rather than individual merit or societal ties raises serious ethical questions:

Individuals with identical achievements may find themselves with vastly different rights and opportunities based solely on the nationality of their grandparents or birthplace.

This “citizenship by birth” approach or “birth lottery” is criticized for producing uneven access to mobility, education, and voting rights—reinforcing global inequity and legacy privilege.

As articulated in Italy’s recent debates: some remote descendants gain visa-free travel and EU membership, while Italy-born children of immigrants remain excluded until adulthood—it’s not just legal oversight, but a reflection of systemic inequality.

✅ Case Studies of Jus Sanguinis in Action

|

Country |

Approach |

Key Rule & Requirement |

Impact |

|

Italy |

Descent-based w/ limits |

Parent/grandparent born in Italy OR residency 2+ years; applications before March 2025 grandfathered |

Removed ~80 M descendants, caused consular backlog & legal backlash |

|

Germany |

Descent + consular registration |

Mandatory birth registration with embassy within 1 year |

Preserves lineage connection but penalizes uninformed families |

|

USA |

Dual system |

Jus soli (14th Amendment, Wong Kim Ark) + jus sanguinis under 2000 law |

Guarantees birthright citizenship; descent requires conditions |

|

India |

From unconditional birthright to hybrid |

Birthright removed in 2004; descent nationality with consular registration |

Tightens nationality, preserves diaspora linkage |

Insights from Case Studies of Jus Sanguinis

Italy’s shift underscores political reaction to administrative strain, highlighting how diaspora-driven citizenship can prompt systemic backlash.

Germany’s model emphasizes lineage authenticity through registration deadlines—striking a balance, yet raising fairness issues.

The USA exemplifies legal robustness, successfully defending birthright citizenship while managing descent-based rights.

India’s evolution reflects demographic and migration concerns—transitioning to a more selective, hybrid system.

International Law & Human Rights Norms

Jus sanguinis — or citizenship by descent — operates within a broader framework of international law designed to prevent statelessness, uphold children’s rights, and ensure gender equality in nationality transmission. Various global conventions, regional policies, and landmark legal cases shape how states implement and regulate ius sanguinis today.

U.N. Statelessness Conventions

The 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, adopted by the United Nations and effective since 1975, is the principal global treaty addressing nationality gaps. It imposes clear obligations on states to ensure individuals are not left stateless — whether by birth, administrative gaps, or political changes.

Key provisions include:

- Nationality at birth: States must grant nationality to anyone born in their territory who would otherwise be stateless, safeguarding children from legal invisibility. Alternatively, they may fulfill this through ius sanguinis by conferring nationality from parents if this ensures the child is not stateless.

- Foundling protections: Foundlings — children found with unknown parentage — are presumed to be nationals of the country where discovered, preventing them from falling outside all national systems.

- Loss and deprivation: The convention strictly limits how states may revoke nationality, especially if such revocation would render an individual stateless. These safeguards also apply to changes in sovereignty or territory transfers, ensuring children in such regions do not become nationality “orphans.”

These obligations have driven numerous states to reform nationality laws, integrate statelessness checks into citizenship processing, and align ius sanguinis frameworks with international human rights commitments.

European Union & Council of Europe Policies

Within the European Union, ius sanguinis is formally recognized and categorized by the European Migration Network (EMN) glossary, which defines it as acquiring nationality by birth based on the citizenship of one or both parents.

The EU generally respects member states’ sovereignty over nationality rules but emphasizes that such laws must not violate broader commitments under:

- The European Convention on Nationality (1997), which outlines fair procedures and non-discriminatory nationality principles.

- The Council of Europe’s Statelessness Index, which monitors gaps in descent-based laws, gender discrimination, and deprivation risks, urging member states to close these legal vulnerabilities.

These instruments ensure that ius sanguinis, while primarily domestic, operates within a shared human rights and anti-statelessness framework across Europe.

U.S. Legal Precedents on Jus Sanguinis & Jus Soli

Wong Kim Ark & Constitutional Birthright: In the United States, citizenship law stands on a dual foundation of jus soli and regulated jus sanguinis.

- The landmark 1898 Supreme Court case, United States v. Wong Kim Ark, upheld that anyone born on U.S. soil (with few exceptions like diplomats’ children) is a citizen under the 14th Amendment, solidifying constitutional jus soli.

- This ruling did not address jus sanguinis directly but became crucial in distinguishing unconditional territorial citizenship from descent-based acquisition.

Child Citizenship Act of 2000

Recognizing globalization and transnational families, the Child Citizenship Act (CCA) of 2000 clarified U.S. jus sanguinis rules. It allows children born abroad to automatically acquire U.S. citizenship if certain residency and legal conditions tied to their citizen parents are met.

The U.S. system thus illustrates how a country can simultaneously honor strong territorial birthright while carefully regulating descent-based citizenship to children born overseas.

Gender Equality Mandates & Global Reform

Historically, many nationality laws linked jus sanguinis transmission to the father alone, reflecting deep patriarchal biases.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), adopted by the UN in 1979, directly challenges these norms. Article 9 mandates equal rights for men and women to pass nationality to their children, urging states to amend discriminatory descent laws.

CEDAW’s influence has been profound:

- Over the past two decades, dozens of countries — including Morocco, Algeria, and Nepal — have reformed their nationality laws to allow mothers equal citizenship transmission rights.

- Yet significant gaps remain; as of 2025, more than 20 states still impose restrictions on maternal descent, perpetuating risks of statelessness for children born under such regimes.

✅ Broader Implications for Jus Sanguinis

By aligning ius sanguinis practices with global human rights standards, countries reduce risks of statelessness, uphold gender equity, and embed citizenship in the international legal architecture that balances ancestry-based identity with universal principles of non-discrimination and child protection.

Real-World Case Studies: How Jus Sanguinis Plays Out

To understand how the principle of jus sanguinis — citizenship by descent — functions beyond theory, it is essential to look at real-world applications. Different countries implement this doctrine in strikingly varied ways, balancing heritage, legal safeguards, and modern migration realities. Below are some vivid national examples that show the strengths, pitfalls, and controversies surrounding descent-based citizenship systems.

Italy: The Near-End of Unlimited Descent

A long legacy of citizenship through ancestry: For decades, Italy maintained one of the world’s most expansive jus sanguinis regimes, allowing descendants to claim citizenship through an Italian ancestor — with lineage tracing back all the way to 1861, the year of Italy’s unification. Under this generous system, great-grandchildren and beyond could become Italian citizens provided they documented their ancestral chain, regardless of how many generations had lived abroad.

This policy made Italy unique in Europe for recognizing a practically unlimited chain of descent, leading to an estimated 80 million people worldwide, mostly across the Americas and Australia, potentially qualifying for Italian citizenship.

Decree-Law 36/2025: The dramatic shift

On March 28, 2025, Italy enacted Decree-Law 36/2025, fundamentally restricting this once-open path. The new law:

- Limits eligibility to those with either an Italian-born parent or grandparent, or a parent who had lived in Italy for at least two years before the child’s birth.

- Ends automatic recognition for great-grandchildren and more distant descendants, cutting off a major avenue used by families across Latin America, the U.S., and Canada.

Backlash, heartbreak, and heated debates

The reaction from the vast Italian diaspora was immediate and emotional.

- The Washington Post captured the anguish of applicants like Jerry Lombardo, who felt “betrayed” after spending years collecting birth certificates and legal affidavits only to see their ancestral citizenship hopes dashed overnight.

- Critics argue that Italy had become a target of “passport shopping,” with consulates overwhelmed by lineage claims that sometimes stretched five or six generations. In online forums like Reddit, debates flared over whether such sweeping descent rights undermined Italy’s national resources.

Still, transitional rules were included: applications filed before March 28, 2025, continue under the old regulations, offering a final chance for families already deep into the bureaucratic process.

Germany: Registration Safeguards in Practice

Controlled descent with administrative rigor: Germany operates a primarily jus sanguinis framework, granting citizenship by descent from German parents regardless of birthplace. However, Germany imposes a strict administrative safeguard:

- If a German citizen has a child born abroad, they must register the child’s birth at a German consulate within one year, or risk the child losing their claim to German nationality.

Balancing lineage and national identity

This rule is designed to avoid creating a population of “citizens-in-absentia” who might never develop genuine ties to Germany. While it strengthens national cohesion, it can inadvertently harm families who, due to distance, lack of awareness, or bureaucratic barriers, miss the registration deadline. Reddit discussions are full of families grappling with retroactive loss of citizenship due to missed paperwork — highlighting the sometimes harsh outcomes of rigid descent protocols.

United States: Dual Principles in Action

The United States uniquely combines unconditional birthright citizenship (jus soli) with carefully regulated citizenship by descent (jus sanguinis):

- Under the 14th Amendment and reinforced by the historic Wong Kim Ark (1898) decision, anyone born on U.S. soil is automatically a citizen, regardless of their parents’ nationality — a principle foundational to American identity.

Jus sanguinis with strict parental requirements

Conversely, U.S. descent-based citizenship is not automatic.

- For children born abroad to American parents, eligibility depends on the citizen parent meeting specific physical presence or residency requirements before the child’s birth.

- Moreover, families must actively pursue passport applications or consular registration for these children to be recognized as U.S. citizens.

This dual framework illustrates how a nation can embrace territorial inclusivity while still imposing checks on descent to maintain meaningful ties.

India: From Unconditional to Hybrid Citizenship

India once had one of the most liberal nationality systems in the world, granting citizenship purely by birth in India — a classic example of unconditional jus soli. This policy, established in the wake of independence, sought to build a cohesive, inclusive nation across deep linguistic and religious diversity.

The 2004 pivot to mixed rules

However, amid concerns over irregular migration and demographic pressures, India revised its constitution in 2004, restricting automatic jus soli.

- Today, citizenship at birth is only available if at least one parent is an Indian citizen — effectively inserting a jus sanguinis element into what was once a purely territorial model.

Modern hybrid with diaspora emphasis

For overseas Indians, India continues to use jus sanguinis rules. Children born abroad to Indian parents generally qualify, provided births are registered in a timely manner. This approach simultaneously addresses local demographic sensitivities while maintaining cultural and economic ties with its vast diaspora.

📝 Insights Across Case Studies

These diverse national examples show that jus sanguinis is far from uniform worldwide. Each country tailors descent-based citizenship to fit its unique socio-political goals:

- Italy is retreating from broad ancestry-based access to protect local institutions and resources.

- Germany enforces administrative rigor to ensure genuine links.

- The U.S. balances birthright inclusivity with controlled descent.

- India shifts between openness and restriction, trying to safeguard domestic stability while nurturing diaspora connections.

Together, these case studies underscore the complex trade-offs inherent in citizenship by bloodline: balancing ancestral ties with current national interests, preventing statelessness without overextending resources, and navigating global mobility in a world where families frequently span multiple borders.

📚 References

Bocci, A. (2025, April 1). Italian citizenship by descent (iure sanguinis): New Decree 2025. Boccadutri.com. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.boccadutri.com/italian-citizenship-by-descent-decree-law-36-2025/ (boccadutri.com)

Italian Citizenship Assistance. (2025, June). Decree‑Law No. 36/2025: Conversion into Law. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://italiancitizenshipassistance.com/decree‑law‑no‑36‑2025‑conversion‑into‑law/ (italiancitizenshipassistance.com)

ItalyGet. (2025, April). Decree 36: Understanding Italy’s Ius Sanguinis Overhaul. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://italyget.com/en/decree-36-tajani-italian-citizenship/ (italyget.com)

Studio Legale Metta. (2025, April). Italian citizenship jure sanguinis – Further restrictions. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.studiolegalemetta.com/citizenship/italian-citizenship-jure-sanguinis-restrictions/ (studiolegalemetta.com)

Consulate of Italy in Adelaide. (2025, June 5). Reform of citizenship iure sanguinis. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://consadelaide.esteri.it/en/news/dal_consolato/2025/06/reform-of-citizenship-iure-sanguinis/ (consadelaide.esteri.it)

United Nations Convention

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (n.d.). 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.unhcr.org/ibelong/wp-content/uploads/1961-Convention-on-the-reduction-of-Statelessness_ENG.pdf (unhcr.org)

United Nations Treaty Collection. (n.d.). Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?chapter=5&mtdsg_no=V-4 (treaties.un.org)

UNHCR Statelessness Resources

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (n.d.). Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. UNHCR US. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/convention-reduction-statelessness (unhcr.org)

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2020, May). Guidelines on Statelessness No. 5: Loss and Deprivation of Nationality under Articles 5–9 of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Refworld. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.refworld.org/policy/legalguidance/unhcr/2020/en/123216 (refworld.org)